Haka

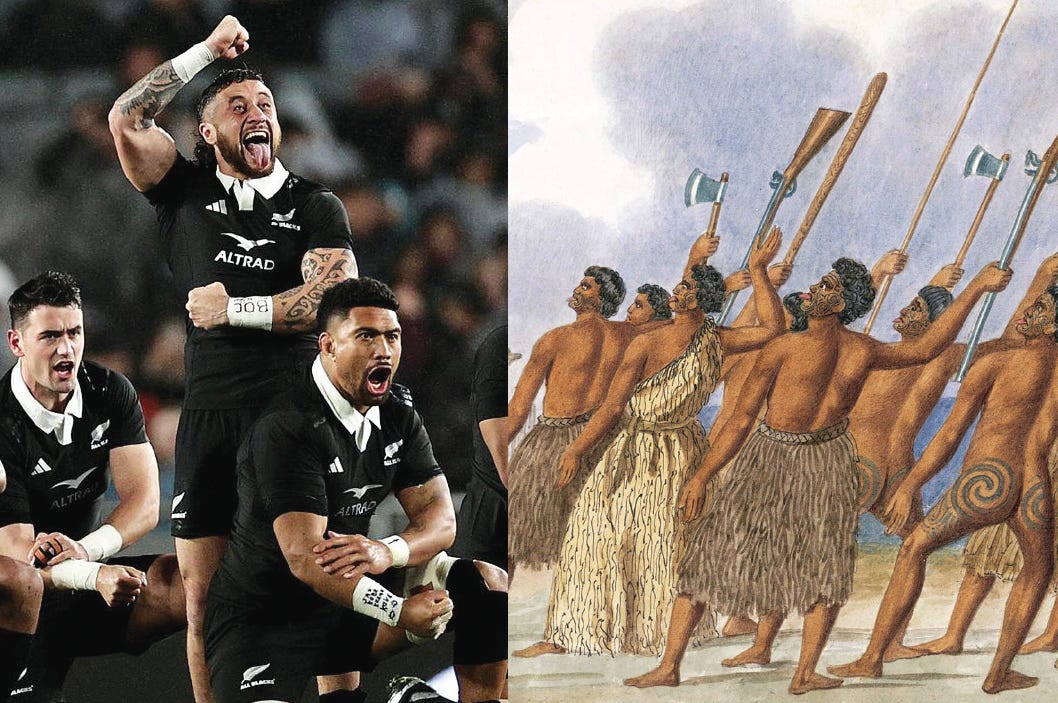

Now very much associated with the New Zealand All Blacks rugby team, the haka has its origins in Māori legend.

Welcome to our inaugural RR5 story preview for September – with full content exclusive to paying subscribers. Enjoy the selection of videos at the base of the post.

NB: Those of you who know me, either personally or professionally, would also know that it’s not in my nature to restrict access to content – but I do need to think of ways to make this publishing project sustainable and properly reward paying subscribers.

Remo

The haka is a powerful expression of Māori identity, culture and unity – a performance tradition that has deep historical roots, retaining strong contemporary significance.

The dance engages the entire body in vigorous rhythmic movements, which may include swaying, slapping of the chest and thighs, stamping and gestures of stylised violence. It is accompanied by a chant and, in some cases, fierce facial expressions meant to intimidate – such as bulging eyes and a protruding tongue. Though often associated with the traditional battle preparations of male warriors, the haka may be performed by both men and women, and several varieties of the dance fulfill social functions within Māori culture.