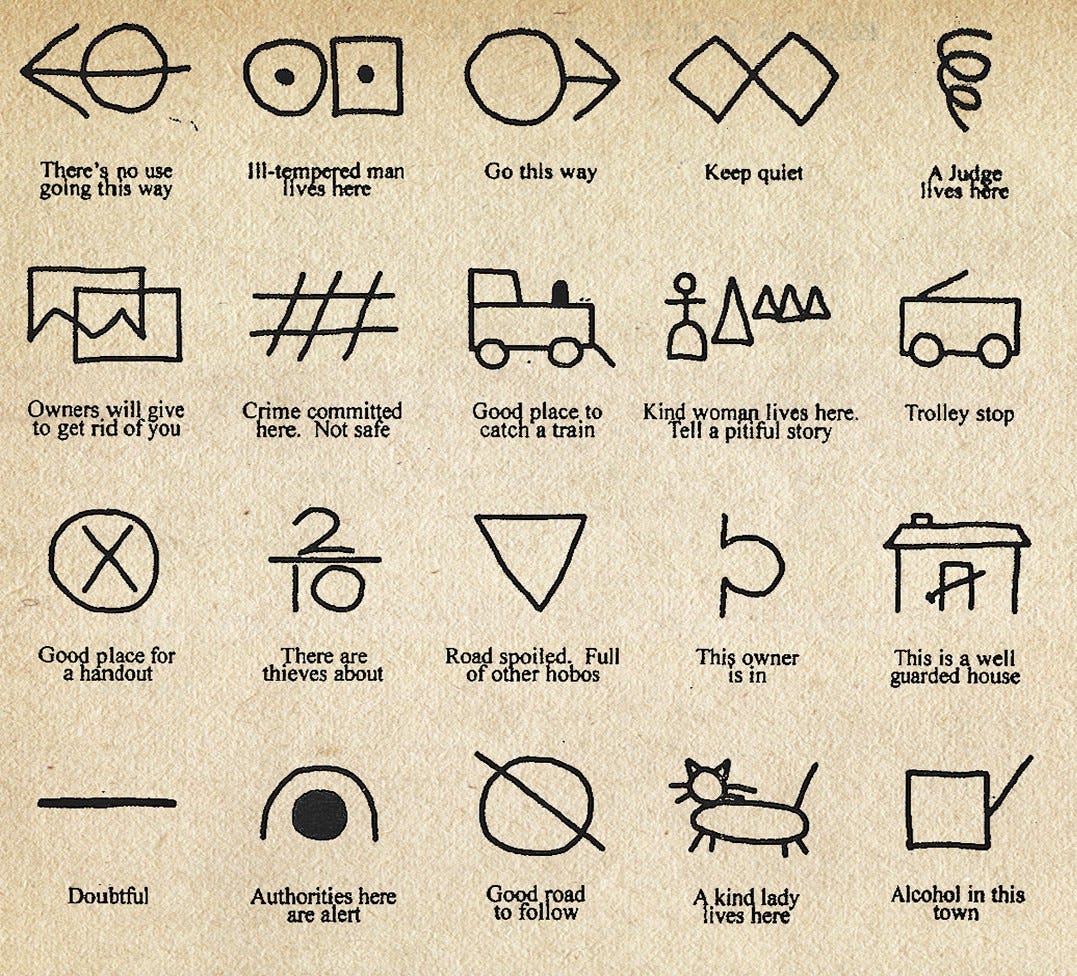

Hobo Code

A pictographic code used by Depression-era itinerant workers helped fellow hobos keep one another safe. These days a QR code may announce the presence of "unexpectedly good coffee".

Hobos (a word that is thought to derive from the term hoe-boy, describing a farm hand) were Depression-era itinerant workers who illegally hopped freight trains and journeyed across the United States, taking odd jobs wherever they could find them. By the early 1900s, it is said that there were more than 500,000 hobos in the US.

The “…