Thatcher Effect

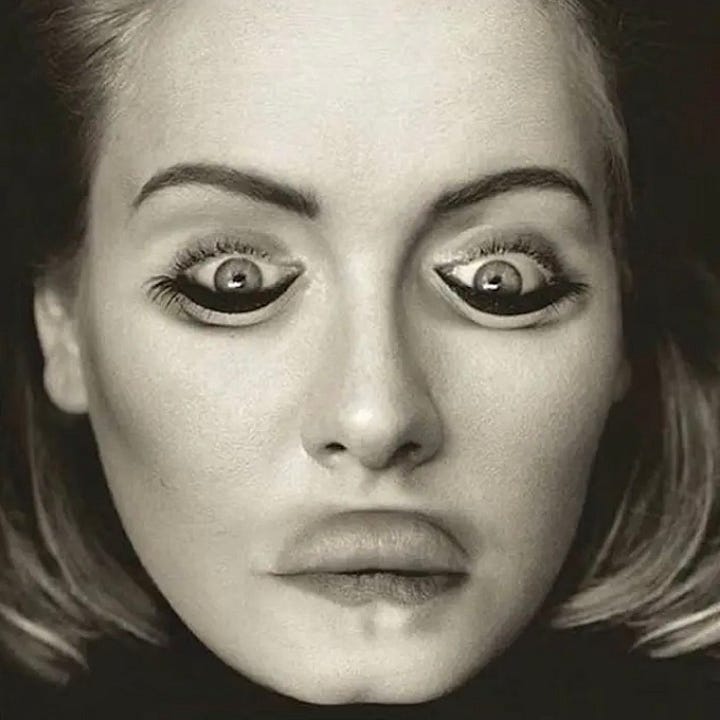

Our brains are specialised for processing faces, but not when they are upside down.

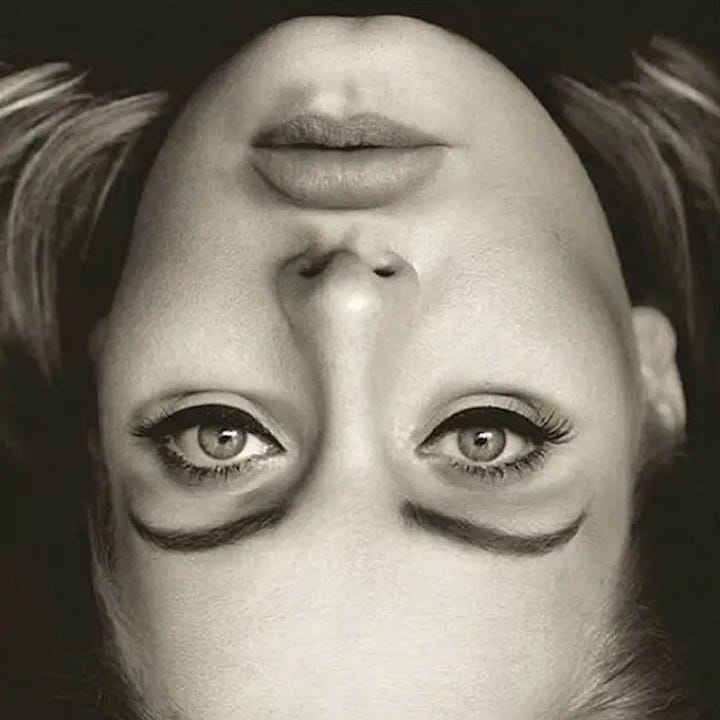

How does the first image of Adele’s face look to you? Anything remarkable, other than the fact that it’s upside down?

While the singer’s face has been turned upside down, her eyes and mouth have actually been left the right way up. As you can see from the adjacent image, the result is something that looks very strange indeed, mesmerising many netizens in…