The Bilbao Effect

The recent death of renowned architect Frank Gehry has inspired me to post this look at a phenomenon associated with what is his most famous project, the Guggenheim Bilbao.

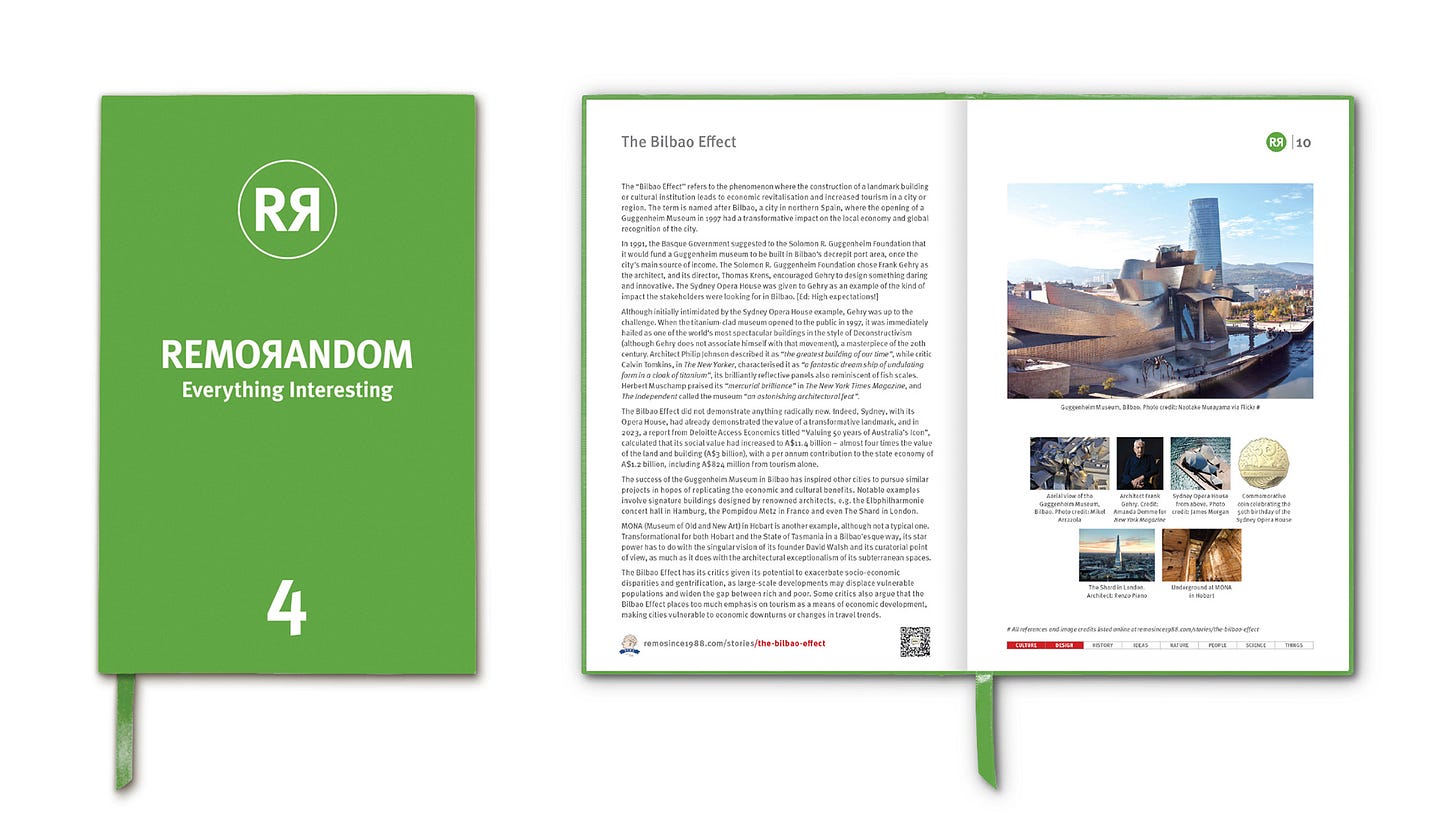

The “Bilbao Effect” refers to the phenomenon where the construction of a landmark building or cultural institution leads to economic revitalisation and increased tourism in a city or region. The term is named after Bilbao, a city in northern Spain, where the opening of a Guggenheim Museum in 1997 had a transformative impact on the local economy and global recognition of the city.

In 1991, the Basque Government suggested to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation that it would fund a Guggenheim museum to be built in Bilbao’s decrepit port area, once the city’s main source of income. The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation chose Frank Gehry as the architect, and its director, Thomas Krens, encouraged Gehry to design something daring and innovative. The Sydney Opera House was given to Gehry as an example of the kind of impact the stakeholders were looking for in Bilbao. [Ed: High expectations!]

Although initially intimidated by the Sydney Opera House example, Gehry was up to the challenge. When the titanium-clad museum opened to the public in 1997, it was immediately hailed as one of the world’s most spectacular buildings in the style of Deconstructivism (although Gehry does not associate himself with that movement), a masterpiece of the 20th century. Architect Philip Johnson described it as “the greatest building of our time”, while critic Calvin Tomkins, in The New Yorker, characterised it as “a fantastic dream ship of undulating form in a cloak of titanium”, its brilliantly reflective panels also reminiscent of fish scales. Herbert Muschamp praised its “mercurial brilliance” in The New York Times Magazine, and The Independent called the museum “an astonishing architectural feat”.

The Bilbao Effect did not demonstrate anything radically new. Indeed, Sydney, with its Opera House, had already demonstrated the value of a transformative landmark, and in 2023, a report from Deloitte Access Economics titled “Valuing 50 years of Australia’s Icon”, calculated that its social value had increased to A$11.4 billion – almost four times the value of the land and building (A$3 billion), with a per annum contribution to the state economy of A$1.2 billion, including A$824 million from tourism alone.

The success of the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao has inspired other cities to pursue similar projects in hopes of replicating the economic and cultural benefits. Notable examples involve signature buildings designed by renowned architects, e.g. the Elbphilharmonie concert hall in Hamburg, and even The Shard in London.

MONA (Museum of Old and New Art) in Hobart is another example, although not a typical one. Transformational for both Hobart and the State of Tasmania in a Bilbao’esque way, its star power has to do with the singular vision of its founder David Walsh and its curatorial point of view, as much as it does with the architectural exceptionalism of its subterranean spaces.

The Bilbao Effect has its critics given its potential to exacerbate socio-economic disparities and gentrification, as large-scale developments may displace vulnerable populations and widen the gap between rich and poor. Some critics also argue that the Bilbao Effect places too much emphasis on tourism as a means of economic development, making cities vulnerable to economic downturns or changes in travel trends.

REMORANDOM Book Chapter