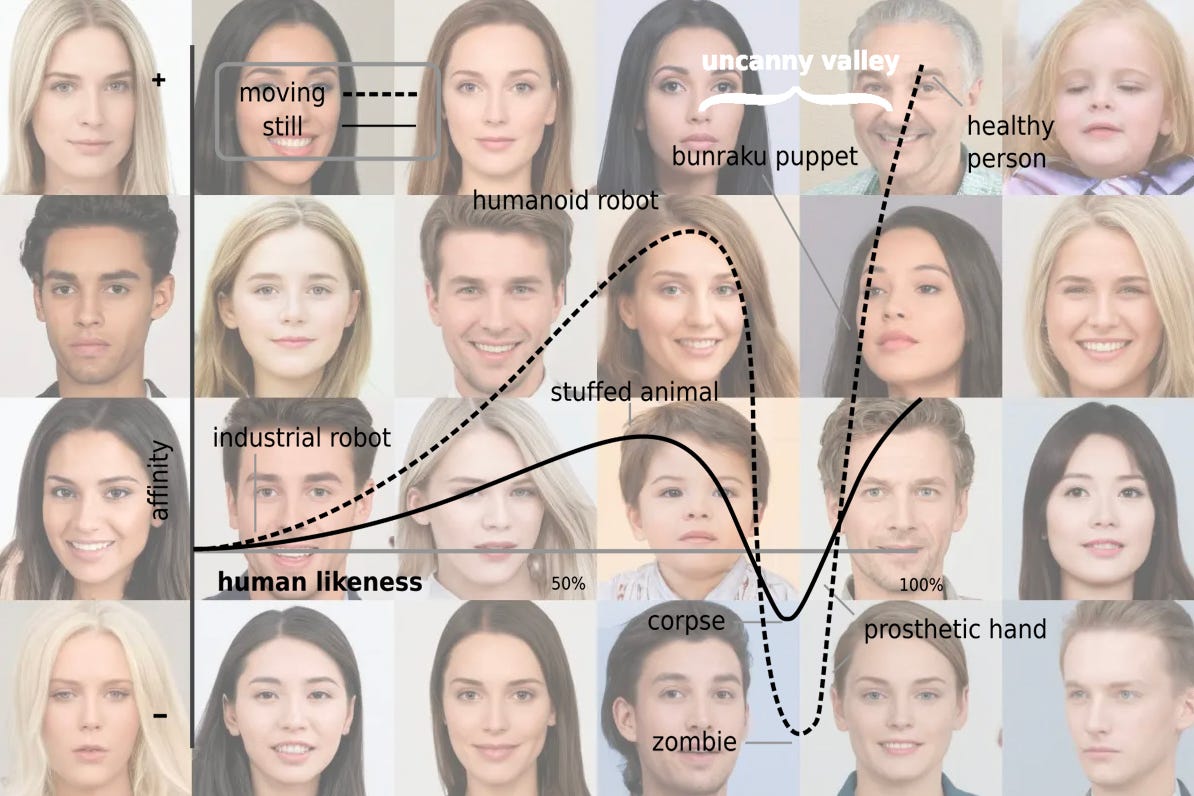

Uncanny Valley

"We're all dwelling in uncanny valley now," writes Maureen Dowd in a 4 October New York Times piece referencing AI-generated actor Tilly Norwood. So, what's "uncanny" – and why is it a "valley"?

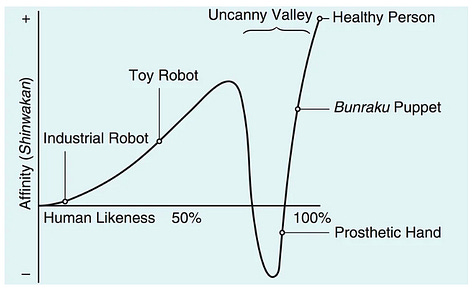

Coined in 1970 by Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori (森 政弘), the term “uncanny valley” describes a dip in emotional comfort when something non-human becomes too close to human, without being really human.

So, looking at the graph that accompanied his thinking, from left to right: a r…