Untranslatable Japanese Words

A woman who appears attractive from behind but not from the front? There's a Japanese word for that.

The Japanese language reflects the zen-like beauty of their culture. There are hundreds of untranslatable Japanese words that have no English counterpart. Here are some of them:

Bakku-shan (バックシャン)

A woman who appears attractive from behind but not from the front.

Bureikou (無礼講)

Where social hierarchies and formalities are temporarily set aside, allowing people to interact freely and without the usual constraints of rank or status. Often used at nomikai (company drinking parties).

Hanafubuki (花吹雪)

Translates as “flower blizzard” or “blizzard of blossoms”. Used to describe how cherry blossom petals float down en-masse, like snowflakes in a blizzard.

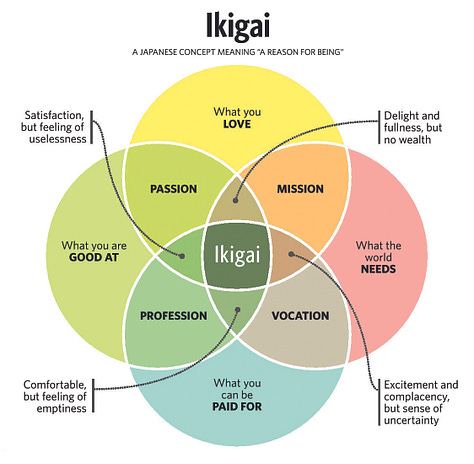

Ikigai (生き甲斐)

Often translated as “reason for being” or “purpose in life”, but is more complex than that. It’s about finding joy and fulfilment in life’s small, everyday things. See Ikigai [RR1:39].

Itadakimasu (いただきます)

A common and deeply cultural phrase traditionally said before eating a meal. It expresses gratitude not only to the person who prepared the food, but also to everyone involved in bringing the meal to the table – from farmers to fishermen, and to the animals and plants that were sacrificed for sustenance.

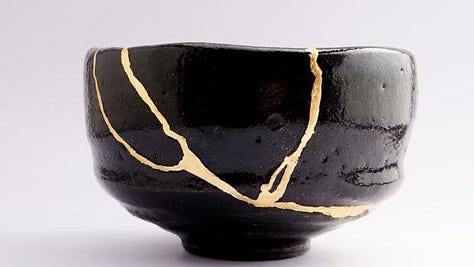

Kintsukuroi (金継ぎ)

A term that translates to “golden repair”. It refers to the art of repairing broken pottery with lacquer mixed with powdered gold, silver or platinum, creating a beautiful and unique mended piece.

Kuchisabishii (口寂しい)

Translates literally to “lonely mouth”. It describes the feeling of wanting to eat or snack, not because of hunger, but out of boredom, habit, or the desire to have something in your mouth. [Ed: Charming.]

Natsukashii (懐かしい)

A Japanese word that encapsulates a warm sense of nostalgia or fondness for the past. Natsukashii has a more positive connotation than the English word “nostalgia”.

Omotenashi (おもてなし)

Refers to the art of selfless hospitality, where hosts anticipate and fulfil the needs of their guests with sincerity and attention to detail, often without the expectation of anything in return.

Shinrin-yoku (森林浴)

Literally “forest bathing”, refers to immersing oneself in nature to promote well-being and relaxation. Benefits both physical and mental well-being.

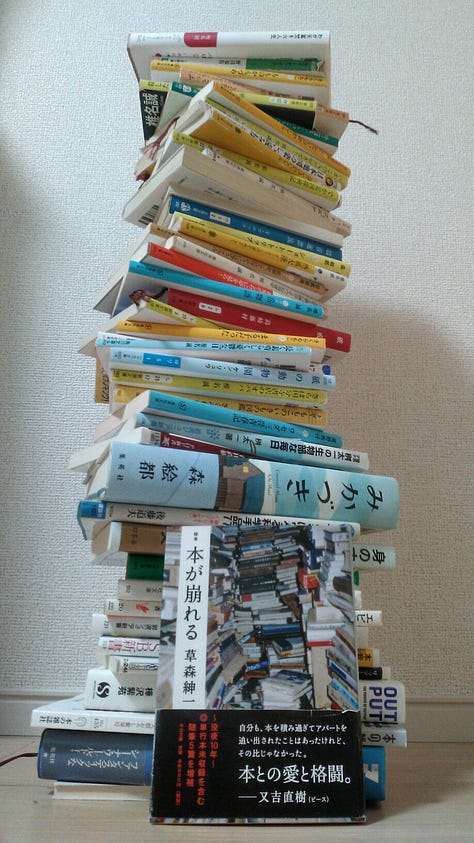

Tsundoku (積ん読)

In English, the untranslatable Japanese word tsundoku describes the act of piling up books that you will never get around to reading.

Wabi-sabi (侘寂)

When you adopt a wabi-sabi perspective, you accept that life is imperfect and, therefore, can appreciate the beauty of imperfect things, e.g. an imperfection purposefully left in an artwork.

REMORANDOM Book Chapters