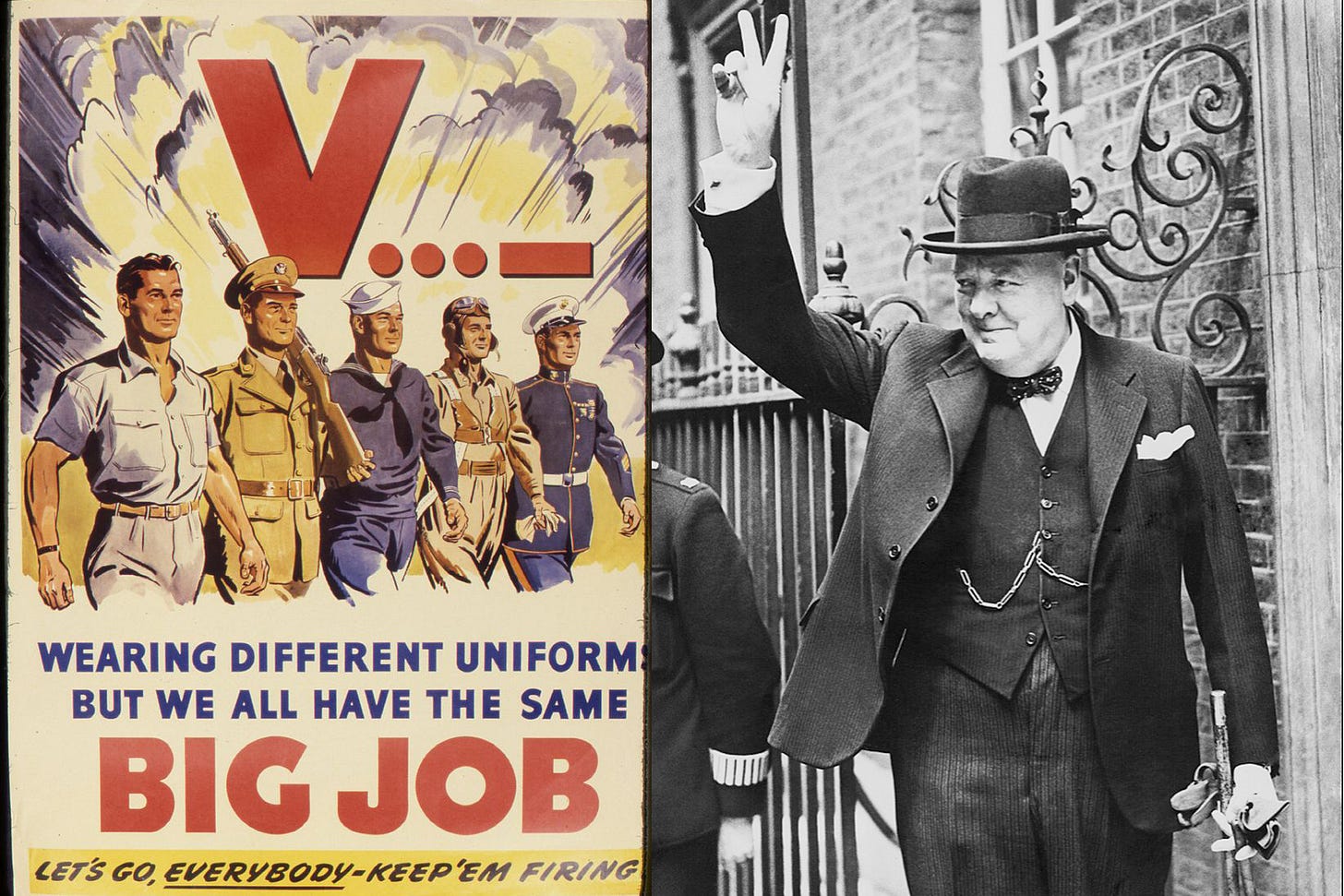

V for Victory

Palm forward! It took a while for Churchill to get it right.

While more widely recognised today as a gesture of peace or triumph, the origins and evolution of the two-fingered “V for Victory” sign have more to do with wartime strategy, political symbolism and defiance.

The gesture as we know it was popularised during World War II. In January 1941, Belgian …